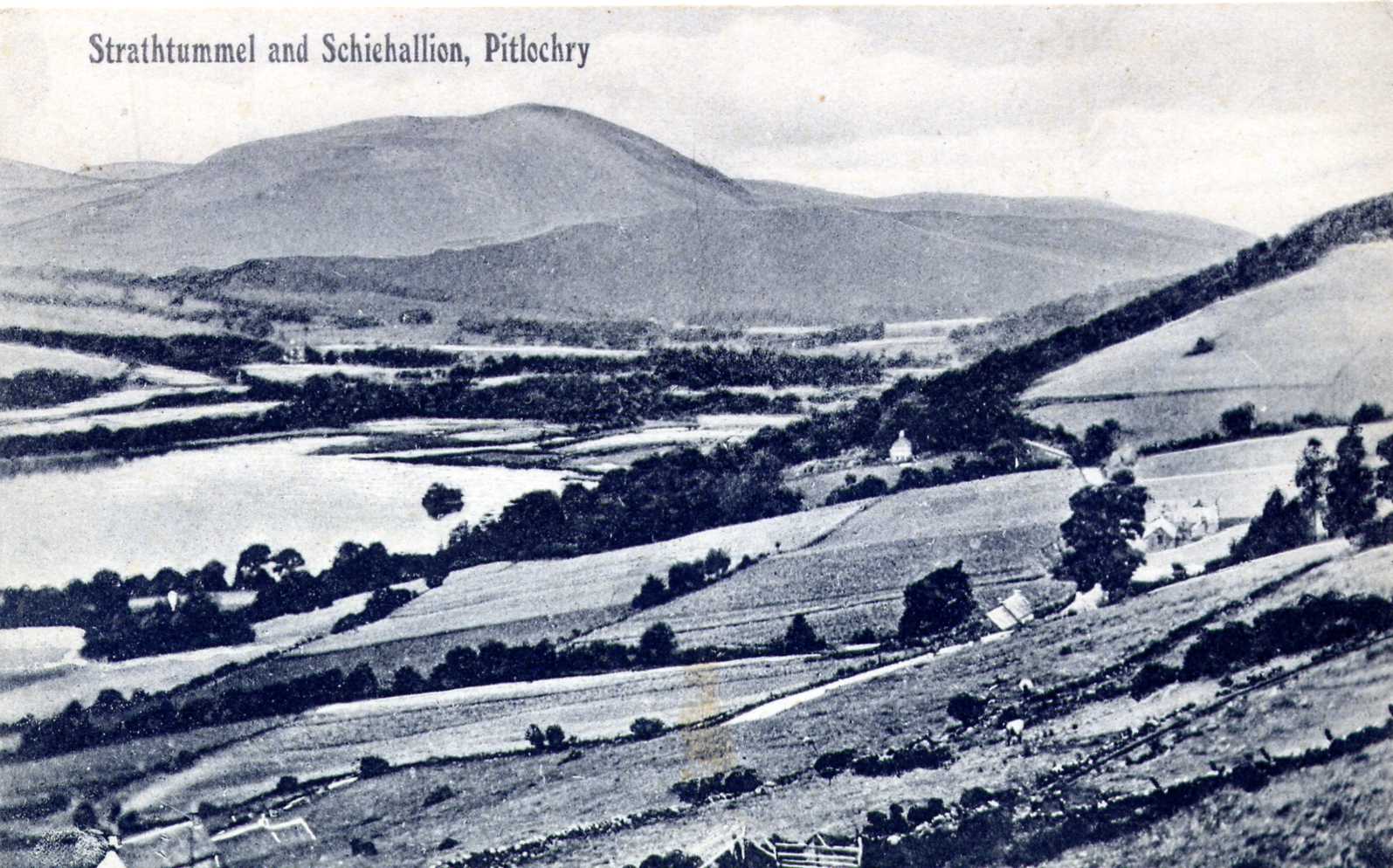

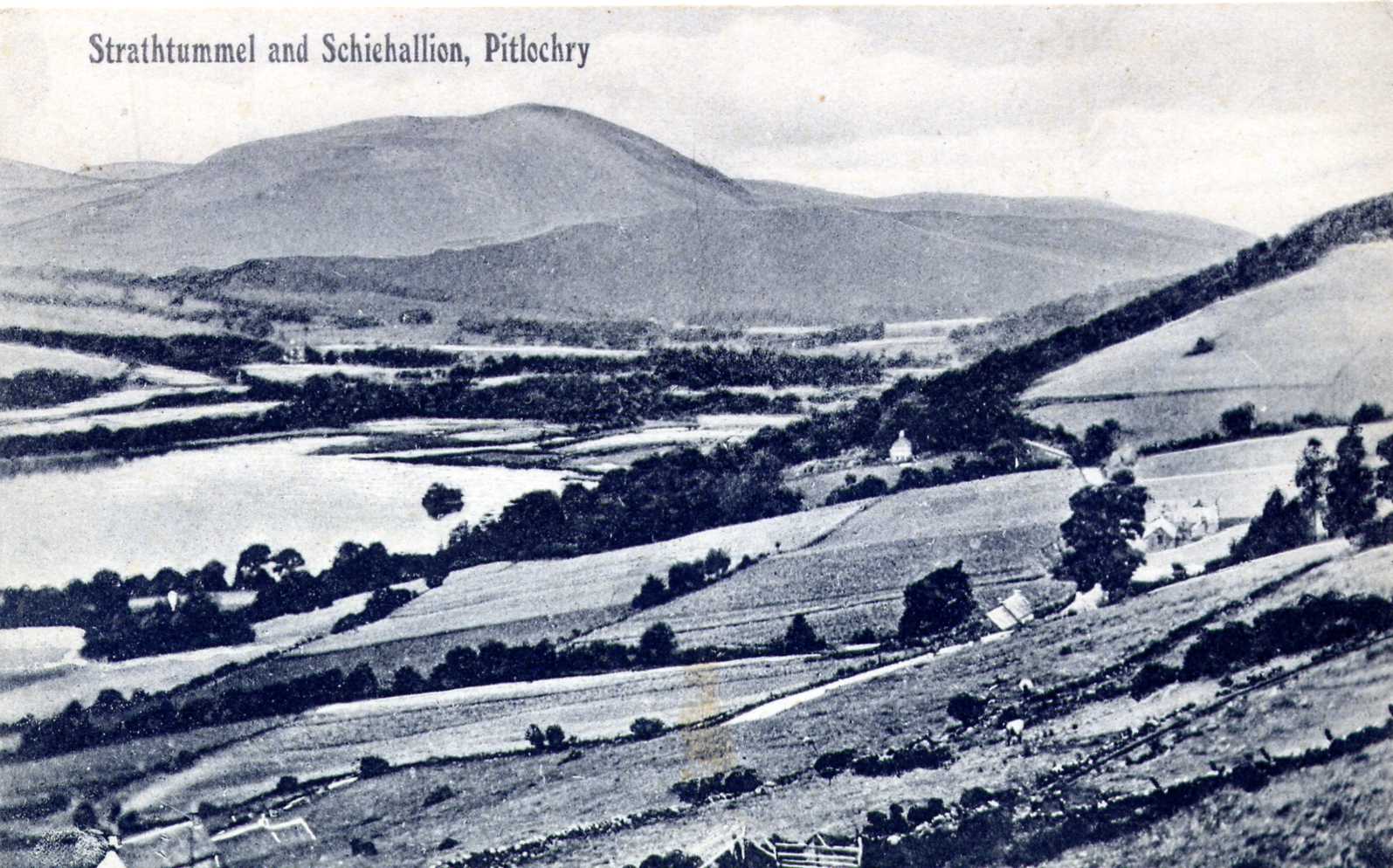

The postcard above shows a small island in Loch Tummel. This is Port-an-eilean which is mentioned in The Old Statistical Account of Scotland: Blair Atholl and Strowan (1792) written by the Rev James McLagan.

In the N.W. corner of Loch Tummel there is a small island, partly artificial, on which Duncan Ravar McDonald, the chief of

the Clan-Donnachie, or Robertson, built a strong house and a garden, which gave the name Port-an-eilein, or the Fort of the

Island, to that place.

Dònnchadh Reamhar or "Duncan the Stout" (as in stout-hearted), who is regarded as the first chief of Clan Robertson (Clan Donnachaidh) was a loyal supporter of Robert the Bruce during the wars for Scottish Independence, and lead his clansmen at Bannockburn (24th June 1314). His crannog stronghold was the centre of Robertson power until July 1515, when it became the property of John Stewart, 2nd Earl of Atholl as recorded in the 'Chronicles of the Families of Atholl and Tullibardine'.

July 27th 1515 - The Earl had a precept of sasine from King James V, investing him with the lands and barony of

Struan; forest and lands of Glengarry; Kirkton of Struan, called the Clachan; Blairfetty; Trinafour; the lands of the two Bohespics;

Innerhadden; Grennich; Port Tressait; Isle of Loch Tummel, with the house thereof; Carrick; Drumnacarf; Balnavert and Balnaguard, - which

lands were apprised by decreet of the Lords of Council from William Robertson of Struan for default of payment of £1,592 Scots, due by

him to the Earl.

Although Port-an-eilean appears to have been more substantial than a simple crannog, by 1783 it had not been in use for some considerable time. James Stobie's 1783 map of Borenich shows Port-an-eilean with the simple comment "castle in ruins".

In 'Additional Notes on Artificial Islands in the Highland Area (1913), the Rev F. O. Blundell reported that Hugh Mitchell had investigated two artificial islands in Loch Tummel - the largest of the two being Port-an-eilean which measured 50 yards by 35 yards at that time.

This island stands in about 7 feet of water, but there is a deep channel between it and the shore. The island is formed of stones,

which seem to rest on trees. What looked like the ends of trees could be seen below the stones. The stones seem to have been carefully

laid — almost as if built in courses — and average about 1 foot square.

He also described a smaller island, 25 feet in diameter, where "the stones are placed closely together and present the appearance of being almost built into their present position. The loch having risen two feet in the last eighty years, has reduced the surface of the island." The accompanying photograph of Port-an-eilean shows no trace of a castle, just trees and thicket.

Unfortunately, when the Clunie dam was built as part of the post-war Tummel-Garry hydro-electric scheme, the rising water level flooded the far end of the loch and submerged the island, so that the island is no longer visible. However, it is worth visiting the Crannog centre, near Killin, on Loch Tay which is run by the Scottish Trust for Underwater Archaeology.

Since 1980 the Trust has been excavating the late Bronze Age/early Iron Age site of Oakbank Crannog. Waterlogging has made the preservation of organic materials spectacular, including the original pointed alder posts of the supporting platform, floor timbers and hazel hurdles forming internal partitions. Using this information the Trust has constructed, as authentically as possible, a full-size crannog which is open to the public.

In the early 1970s, during maintenance work on the Clunie dam, the water level was lowered and the submerged island was briefly exposed. Mrs Torry at Port-an-eilean House, which was a hotel at the time, saw stone slabs on the north side of the island, which she thought were steps leading down to a crossing point. There was a photograph of the island in the dining room of the hotel, but this now seems to have been lost.

During the survey of Perthshire crannogs in 2004, Dr Nick Dixon and colleagues from Edinburgh University dived at the site.

The top of the site is now three metres under water and is covered with the stumps of trees cut down before submergence. The remains are

still very obvious of a well-made flagstone floor with a path leading to a flight of steps that went down to the loch bed, some two metres

deeper.

Most Scottish crannogs appear to have consisted of a single thatched roundhouse, deliberately built out in the water for protection from wild animals and invaders. Based on the results of Nick Dixon’s underwater surveys and excavations, we now know that the crannogs were built as free-standing timber pile-dwellings in the lochs of woodland environments, and as circular or sub-circular stone buildings on man-made or modified natural rocky islands in more barren environments. They were occupied as early as the Neolithic period, some 5,000 years ago, until the 17th century AD.

| Return to Strathtummel in Past Times | Return to Home Page |

|---|